Building Memory Systems that Learn Across Conversations

How to create AI systems that adapt and improve their performance over time by learning from past interactions. Going over the MemGPT and Letta AI frameworks approach on bulding agents with memory systems that evolve through conversations.

Building Memory Systems that Learn Across Conversations

We’re living through a rapid shift in how software is built. With the rise of AI agents, systems can now plan, reason, and iteratively improve their outputs in ways that were impractical just a year ago.

A lot of progress has been made on how agents think.

Much less progress has been made on how agents remember.

This gap matters more than it first appears. Imagine telling your travel agent that you can’t eat spicy food, only to have it enthusiastically recommend a Sichuan restaurant in the very next conversation. Or mentioning that you hate cold weather, then getting pitched a ski trip the following day. The agent has every tool it needs to plan perfectly, but without memory, it’s meeting you for the first time. Every single time.

An agent that can reason through a complex problem but forgets everything it learned afterward is fundamentally limited. A “personalized” assistant that requires you to restate your preferences in every conversation isn’t really personalized at all.

Today, most systems approximate memory using conversation history or retrieval-augmented generation. These techniques are useful, but they are not memory systems. They store information, but they don’t let agents learn across conversations.

This led me to dig deeper into what a real agent memory system requires. In this post, I’ll look at early approaches such as MemGPT, how those ideas evolved into frameworks like Letta, and what design trade-offs they introduce. I’ll also build a small, practical memory system to explore how real agentic systems can persist identity, preferences, and learned behavior over time.

Thinking is only half the problem. If we want agents that improve, memory has to be treated as a first-class concern.

MemGPT

I’ll start explaining building the memory systems from the research standpoint. MemGPT was one of the first attempts on solving the agent memory, and the rest of this blog is heavily linked to its research.

Why we need memory in the first place? The reason is simple, LLMs have limited context window, and even if that was limitless, the LLMs are better at recalling information from the start of the prompt or from the end of the prompt. The context window is your most valuable asset, for building great agentic systems, the context window should be optimized to only contain information relevant to the task at hand.

This attempt to only keep relevant information in the context window is the hard part, as in normal chat conversations, we just append new messages to the list of messages.

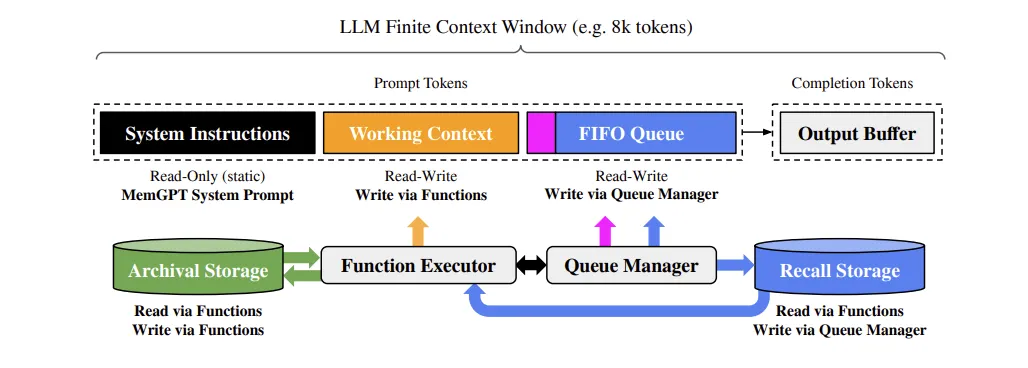

However, operating systems also need memory, and we can utilize learning from building OS memory systems also for the agents. The basic idea of the MemGPT paper was this: build a memory system that reuses this concept of OS memory, by introducing the “virtual memory for the LLMs”.

Virtual Memory Approach

The memory of the agent can be thought of as similar to the OS virtual memory. The agent has a limited context window (like RAM), but it can offload less relevant information to a larger, slower storage (like disk). When the agent needs to recall information, it can retrieve it from this external memory.

So the basic idea is to have a “main memory” that agent can always see, and an “external memory” that agent can be queried to fetch the actual information.

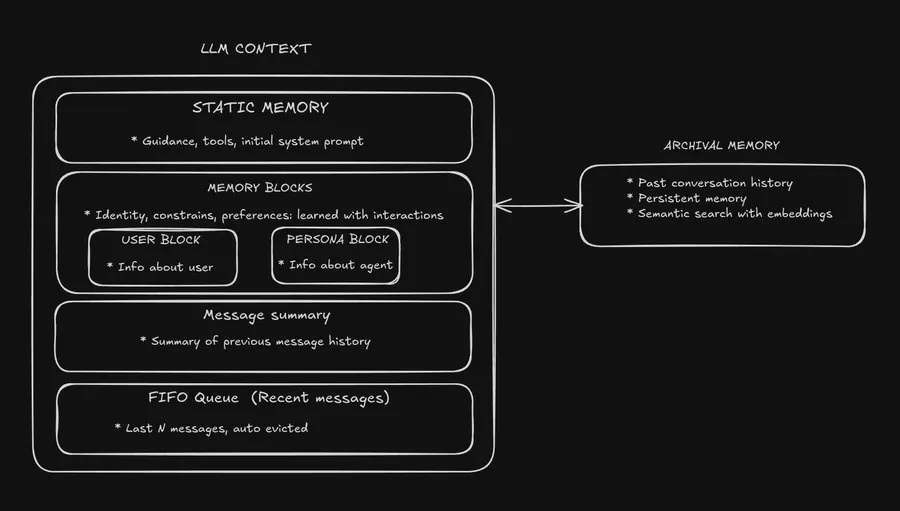

MemGPT memory system consists of multiple different parts of the memory. In the picture above, basic blocks of the memory are shown. The system consist of the main memory, which is also divided to it’s own blocks, and two external memory storages.

Main Memory

The main memory (the prompt tokens) consist of three different parts.

- System instructions

System instructions is the part where the non-changing information is set, e.g. what is the goal of the agent, what tools agent has etc.

- Working context

Working context is memory block, that the agent itself handles. We can think of it as block in the prompt that agent modifies. This will consist of the information that agents want to remember in the interactions, for example, store the basic user information and user’s preferences, store the persona of the agent, store the gathered information that we have from the task at hand.

Agent is given tools that automatically can change the working memory in the prompt, for example:

For example, in my application, I created simple tool for agent to use the memory:

tool({

description: "Update a memory block. Use 'replace' to rewrite entire block, or 'append'/'prepend' to add content without replacing. IMPORTANT: Check the current memory block content (shown in system prompt) BEFORE appending to avoid duplicates. If info already exists, don't append it again.",

inputSchema: z.object({

block: z.enum(["user", "session"]).describe("Which memory block to update: 'user' (persistent profile) or 'session' (temporary conversation state)"),

action: z.enum(["replace", "append", "prepend"]).describe("Action: 'replace' = overwrite block, 'append' = add to end, 'prepend' = add to beginning"),

content: z.string().describe("Content to write to the memory block"),

}),

execute: async ({ block, action, content }) => {

// Code

}),Agent is given this tool + the instructions in the system instructions to use the working memory to store information that is relevant for the task.

- FIFO Queue

First In First Out queue is the part of the memory, that stores the recent interactions. When user interacts with the agent, the messages are stored in the database, and to keep the context window limited, only the most recent N messages are kept in the prompt. This way, agent can always see the recent interactions, and use that information to guide its actions.

The memory also contains the summary of the past interactions, which is stored in the working memory, and saved after by the agent by the pressure from the FIFO queue (more on that later).

Recall Memory

For the memory system to work, we also need to external memories that we can save. One is the FIFO queue messages, e.g. the message history. This is the “Recall storage” in the picture.

Recall storage is memory where the messages are automatically stored after user interactions. So the agent itself doesn’t need to manage storing messages to the recall memory. In the MemGPT, we also give tools for querying this database by certain criteria, e.g. querying by the time, so the agent has ability to find old user messages from the database if ever needed.

FIFO queue itself is just part of this memory, as agents have limited context window, so we only store the most recent messages from the recall storage in the prompt itself.

Archival Memory

The messages itself contain all the information that user has said, but that can be hard to search for the agent, e.g. for agent to know user information, or some attachments to the task in hand, it would need to know what user message contained this information and how to query that. That is inherently a hard task.

Thus, we also need a memory solution that agent itself can control, and that is the “archival memory”. Archival memory is memory that the agent has tools to interact with. When agent gets information that it needs to remember, it can save that information to the archival memory. Everything that is saved to the archival memory is then vector embedded, and agent is given tool to search semantically this database for relevant results.

For this, I created simple tools that agent can use to both save information, and query the same information:

export function createArchivalMemoryTools(userId: string) {

return {

archival_memory_insert: tool({

description: "Store information in long-term archival memory for later retrieval. Use this ONLY for: (1) Past trip itineraries and details, (2) Conversation summaries, (3) Reference information. IMPORTANT: Do NOT use for user profile info (use memory_update with block='user' instead). Before inserting, search archival_memory_search to avoid duplicates.",

inputSchema: z.object({

content: z.string().describe("The information to store in archival memory"),

metadata: z.object({

messageType: z.string().optional().describe("Type of information (e.g., 'trip_itinerary', 'conversation_summary', 'destination_info')"),

sourceMessageId: z.string().optional().describe("ID of the message this came from (optional)"),

}).optional().describe("Optional metadata for better organization and retrieval"),

}),

execute: async ({ content, metadata }) => {

// Internal logic

}),

archival_memory_search: tool({

description: "Search archival memory for information semantically similar to the query. Returns up to 10 results per page.",

inputSchema: z.object({

query: z.string().describe("The search query - describe what you're looking for in natural language"),

page: z.number().optional().default(1).describe("Page number (default: 1, each page has 10 results)"),

}),

execute: async ({ query, page }) => {

// Internal logic

}),

};

}How to use both of these external memory solutions is explained in the static prompt of the agent.

Backpressure from FIFO to Working Memory

Last part of the implementation is how to keep the working memory relevant, and not to overflow the context window. As the working memory is the part that agent itself controls, it can grow indefinitely if not managed.

Each message interaction is stored to the FIFO queue, and when the total context window size exceeds certain limit, e.g. 50k tokens, the memory system sends a system message to the agent, warning it that the working memory has exceeded a certain threshold (70% of the context window). Agent is given instructions in the system prompt to store relevant information from the FIFO queue to the working memory, by summarizing the old summary + the recent messages in the FIFO queue.

Basically, in the system we have one block of memory that is the summary of the past interactions, that gets updated each time the working memory exceeds the threshold. So the system also keeps sending hints to the agent of its own status, and makes it easier for the agent to manage its own memory.

I handle this summary update on message eviction:

private async performEviction(

state: MemoryState,

allMessages: ChatMessage[]

): Promise<void> {

// 1. Calculate current token usage

const systemPromptTokens = TokenCounter.estimateTokens(FULL_SYSTEM_PROMPT);

... // rest of the code

// 2. Calculate target token usage to leave buffer after eviction

const targetTokens =

MEMORY_CONFIG.MAX_CONTEXT_TOKENS * MEMORY_CONFIG.EVICTION_TARGET;

... // rest of the code

// 3. Remove oldest messages until we've freed enough tokens

const evictedMessages: ChatMessage[] = [];

let tokensFreed = 0;

for (const item of messageTokens) {

if (tokensFreed >= tokensToFree) break;

evictedMessages.push(item.message);

tokensFreed += item.tokens;

}

// 4. Generate summary (old summary + evicted messages)

const newSummary = await this.summaryGenerator.generateSummary(

evictedMessages,

state.summary || undefined

);

// 5. Save summary

await this.summaryService.save(newSummary, evictedMessages.length);

// 6. Reset warning flag

await this.queueService.resetWarning();

}Letta AI and Memory Blocks

The MemGPT paper laid the groundwork for thinking about memory systems in AI agents. However, giving agent tools to control memory doesn’t make it easy for the agent if memories that are saved are just random strings in random order.

To fix this, the authors of the MemGPT paper from the Letta AI (LLM memory solution) uses the concept of memory blocks. Instead of thinking the memory in terms of single facts or single messages, we store the information in coherent blocks where similar information is stored.

So in terms of our working memory, instead of having that memory be continuous block of random facts that are stored, we give the stored information a structure.

For example, if agent wants to store information about the user to the working memory, it stores that information to the

We can generate as many blocks as we want, given the problem at hand. For example, we could have

What is great about this is that we can also reuse blocks if we want! For example, in my application, I can store the “persona” and “user” blocks and reuse them for every conversation that the user initiates. If I start new conversation with the user, I can just start with empty task-info block, but reuse the user and persona information from the earlier conversations. Memory this way becomes shareable.

So in my system, agent works with the working memory in terms of blocks, that it can update:

export function createMemoryTools(chatId: string, userId: string) {

return {

memory_update: tool({

description: "Update a memory block. Use 'replace' to rewrite entire block, or 'append'/'prepend' to add content without replacing. IMPORTANT: Check the current memory block content (shown in system prompt) BEFORE appending to avoid duplicates. If info already exists, don't append it again.",

inputSchema: z.object({

block: z.enum(["user", "session"]).describe("Which memory block to update: 'user' (persistent profile) or 'session' (temporary conversation state)"),

action: z.enum(["replace", "append", "prepend"]).describe("Action: 'replace' = overwrite block, 'append' = add to end, 'prepend' = add to beginning"),

content: z.string().describe("Content to write to the memory block"),

}),

execute: async ({ block, action, content }) => {

// Internal logic

},

}),

memory_clear: tool({

description: "Clear a memory block. Use with caution - clearing 'user' will erase the persistent profile. Clearing 'session' resets conversation state (user profile is preserved).",

inputSchema: z.object({

block: z.enum(["user", "session"]).describe("Which memory block to clear: 'user' (persistent profile) or 'session' (temporary conversation state)"),

}),

execute: async ({ block }) => {

// Internal logic

}),

};

}For my playground travel application, I for now introduced only two blocks: user information block, and session information block (to store information about the travel task at hand).

Hard Parts of the Memory

The actual implementation, e.g. creating databases and tools for the agent to store information, or creating embeddings for the stored messages is quite straightforward.

However, harder part is to actually make the agent use the memory system correctly. And for this problem, there is no single best answer on how to do this.

First of all, we need to make both the system prompt and the tools good. As for any task for the agent, the easier for it is to use the tools and easier it is for agent to know how to use the tools, the better the results. In my system prompt, I explain all these tools and when to use each of them, in order the agent to use them at correct places on correct times.

After all, if we give tool, but agent uses them too much or too little, the outcome of the system is bad. In my first iterations without memory blocks and worse system prompt, the agent had problem of not storing the information proactively to the memory. So even if user said some important information about themselves, the agent did not always save that information.

But being too aggressive on the storing the information also makes it possible that agent stores information that not really relevant, or even should be forgotten.

Also querying the database is a problem. As our agents has tools for querying, we would wish that agent would use this capability when trying to answer users questions. But agent doesn’t really know when it should query and when not, agent working memory doesn’t have all the information all the time, so agent should be actively forced to use tools to query if archival memory or older messages contain relevant information on the task at hand.

This is something I still struggle with my implementation, it is hard to find the balance for agent tool use. And this is also a feature that is possible to be made better. For example, using “pressure” system messages to the agent when it tries to answer user question without trying to use the memory tools for prolonged times.

Here are heuristics that I’ve found helpful:

If the agent didn’t act on the information twice, don’t store it. Most agents are too aggressive about saving trivial details. If a user mentions they’re from Finland, that’s worth remembering. If they mention a random fact about a museum they might visit, it’s probably not. The threshold should be: “Would the agent need this information to answer a reasonable follow-up question?”

Every memory must justify its future retrieval. Before storing, the agent should ask: “When exactly would I retrieve this?” If there’s no clear scenario where this memory would be queried, it’s noise, not signal. Most memory systems fail because they’re optimized for storage, not retrieval.

System reminders are a powerful lever. Agents easily forget to use memory tools proactively. Giving the system a voice to nudge the agent “memory is 70% full, compress important info” or “you haven’t queried archival memory recently”, works better than hoping the agent remembers to check. The system should tell the agent what’s happening.

Memory needs bureaucracy to work. Without structure, agents store flat, unorganized data that’s impossible to query effectively. That’s why memory blocks matter: they create a schema the agent can reason about. A <user> block for persistent preferences, a <session> block for temporary context,this structure lets the agent know where information lives and when to use it.

Conclusion

In this post, I went through the basics of building memory systems, and created a MemGPT Inspired memory system for my own agentic application. Thinking about memory in different levels, e.g. main memory, recall memory, and archival memory, helps to structure the problem of building memory systems.

And adding structure to the working memory by introducing memory blocks makes it easier for the agent to both store and retrieve information. However, the hard part was never the implementation, but how agent achieves to use the memory system correctly. Here’s a small video showcasing my agent remembering my previous interactions across multiple sessions:

The outcome is promising, but there is still a lot of room for improvement. I definitely prefer my agent with memory over the one without it. Building memory systems that learn across conversations makes the agents more useful, personalized, and capable of handling complex tasks over time. The progress has been made on the “thinking” side of the agents, the memory is still an open problem.

The infrastructure exists. The challenge now is making it work in practice.