Teaching LLM to improve its own prompts

Building GEPA prompt optimizer from scractch to optimize compound AI system prompts using DSPy framework.

Teaching LLM to improve its own prompts

When working with LLM systems, the biggest bottleneck isn’t about writing the first prompt, but how we can improve it! Real systems rarely rely on single prompt, or single LLM call. They are chains of calls, with many modules interacting with each other. Trying to improve manually feels like:

- editing one prompt accidentally broke another

- changing single line now causes bugs in other parts of the system

- evaluating the performance of the system needs hundreds (or more) examples

- and all of this costs money!

This makes prompt engineering for real systems quite tedious, slow and expensive.

At work, I’ve been able to optimize prompts in a more “machine-learning-driven” way using DSPy, a declarative framework for building modular AI systems that can automatically tune prompts for different components.

However, the way these optimizers actually work has always felt a bit mysterious to me. So I decided to dig deeper and build one of the best prompt optimization algorithms: GEPA

This post is about what I learned while doing that:

- how prompt optimizers really work under the hood,

- how they “compile” better instructions automatically,

- and how surprisingly simple the core ideas become once you implement them yourself.

In this post, I’ll show how GEPA can automatically discover better prompts for multi-module AI systems, and what happens inside this optimization loop.

Generic Pareto (GEPA)

I chose to implement GEPA (Generic Pareto) because it is one of the popular prompt optimization algorithms available in DSPy. The original GEPA paper can be found here.

The paper itself is quite dense, so I’ll break down the key algorithms and concepts in a more digestible format.

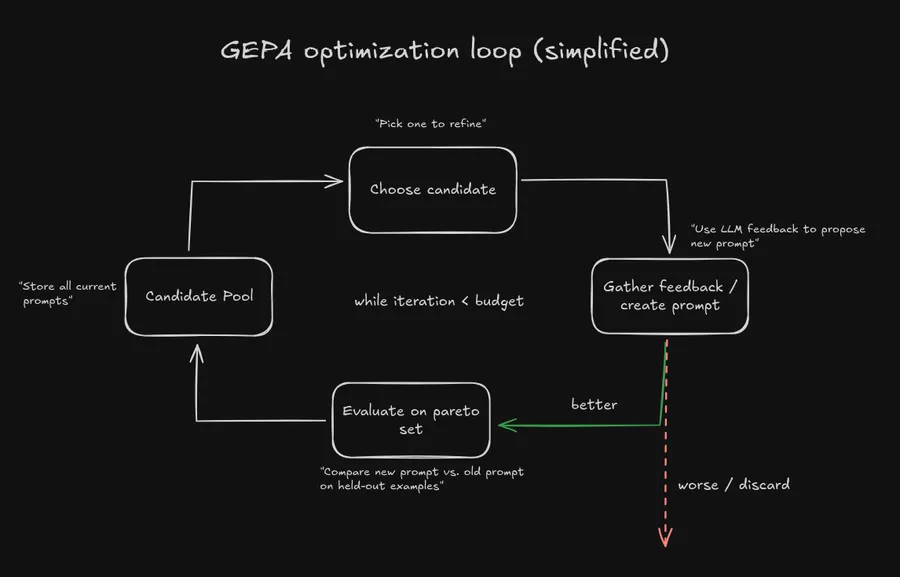

By looking at the GEPA algorithm from a high level, we can see that it consists of two main algorithms:

- Prompt Optimization Loop: This is the main loop that iteratively improves the prompts based on their performance.

- Candidate Selection: This algorithm selects the next candidate prompt to improve upon.

Main loop

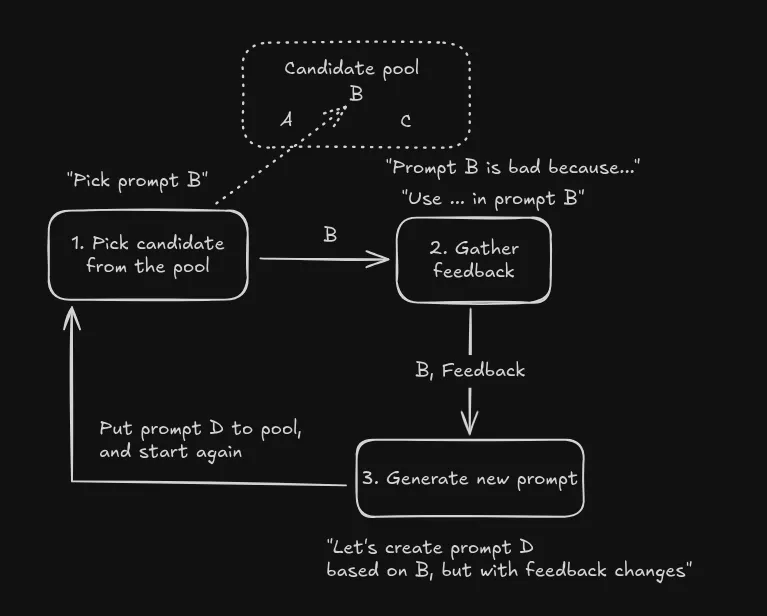

The basic idea is that we have single main loop that we run each iteration. We gather a set of candidate prompts (initially just the base prompt), choose one of them to improve, generate feedback on how to improve the candidate prompt, and then create a new candidate prompt based on the feedback.

As you can see, the core of the algorithm is suprisingly simple:

- We have list of candidate prompts, e.g. A,B,C

- We select one of them, e.g. B

- We generate feedback on how to improve B

- We create a new candidate prompt D based on the feedback

- We add D to the list of candidate prompts if it is better than prompt B.

This loop continues until we reach “budget”, the maximum number of iterations we want to run.

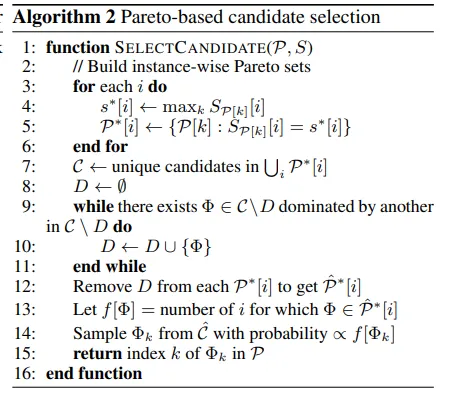

Candidate selection

Another algorithm, and where the GEPA gets its name is the algorithm for choosing the next candidate (prompt) to improve on. The name comes from the “Pareto front”. In simple terms, a Pareto front is just the set of prompts that are not clearly worse than any other prompt across all metrics. If one prompt is better in one metric but worse in another, both can stay. A prompt is only removed if there exists another prompt that is at least as good in every metric and strictly better in at least one.

How I understood that is, for prompts, we have multiple ways we can give “value” for the prompt. Some prompts are good in different metrics, one prompt might have best precision, one best accuracy, one might give the best performance in edge cases. So we have optimization problem, where we have more than one metric we want to optimize for.

So pareto front, is just set of these prompts where there is no other prompt that is best in all the metrics!

Let’s give an example:

| Model | Quality (↑ better) | Cost (↓ better) | Pareto-Optimal? | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 70 | 1 | ✅ | No other model is better or equal in both quality and cost. |

| B | 80 | 2 | ✅ | Higher quality than A, slightly higher cost; not clearly worse than any. |

| C | 90 | 5 | ✅ | Best quality; although expensive, nothing is better in both metrics. |

| D | 85 | 5 | ❌ | Dominated by C (C has higher quality for same cost). |

| E | 60 | 4 | ❌ | Dominated by B (B has higher quality and lower cost). |

Pareto front = { A, B, C }

These are the options where you cannot improve one objective (quality or cost) without making the other worse.

So for the GEPA, we want list of prompts that are pareto front, and then pick one of these prompts in each iteration. And the final choosing of the prompt is also simple: We give some single metric value (e.g. in the table example Quality _ 0.5 + Cost _ 0.5), based on the values, give the higher values bigger chance to be picked, and then just choose one randomly based on the chances! This way, better prompts have better chance to be randomly picked, but we do not always take the best one because the prompt chosen is just by random luck!

Implementation

Now that we have the high level understanding of how GEPA works, let’s see how we can implement it from scratch!

What are we optimizing?

The original GEPA paper optimizes many different tasks, but for simplicity, I chose to optimize HotpotQA task. HotpotQA is a question answering task where the model needs to answer questions based on given context paragraphs.

So I created datatype to represent the example in HotpotQA:

class Example(BaseModel):

qid: str

question: str

context: List[Tuple[str, List[str]]] # [(title, [sentences])]

gold_answer: Optional[str] = None

gold_supports: Optional[List[SupportRef]] = NoneWhere the question is the thing we want to find out, and the context is list of paragraphs where the answer can be found. For the simplicity, I also builded the most simple multi model DSPy module for the task:

import dspy

from .signatures import Reason, Verify

class HotpotModel(dspy.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.reason = dspy.ChainOfThought(Reason)

self.verify = dspy.Predict(Verify)

def forward(self, question: str, context):

r = self.reason(question=question, context=context)

v = self.verify(question=question, context=context, rationale=r.rationale, candidate=r.candidate)

return { "rationale": r.rationale, "candidate": r.candidate, "answer": v.answer.strip() }where the signarutes are simple base prompts that we intend to optimize for

class Reason(Signature := dspy.Signature):

"""From HotpotQA context, identify the bridge fact(s) and propose an answer.

Keep rationale to 2-4 lines. 'candidate' is a SHORT span."""

question = dspy.InputField()

context = dspy.InputField()

rationale = dspy.OutputField(desc="2-4 concise lines showing hops")

candidate = dspy.OutputField(desc="short answer span")

class Verify(Signature := dspy.Signature):

"""Verify or correct the candidate using the context and rationale.

Output ONLY the final short answer span."""

question = dspy.InputField()

context = dspy.InputField()

rationale = dspy.InputField()

candidate = dspy.InputField()

answer = dspy.OutputField(desc="short answer span")So basically, the system is just one call to say rationale of choosing answer, the second one just to verify. I could do the system with only the Reason call, but that way the algorithm would only try to optimize one prompt. For the sake of learning to optimize compound AI systems, I added the verify step so the task corresponds more to the compound AI systems.

Pareto-based candidate selection

Here’s the actual algorithm used in the paper.

Here the P is the list of candidate prompts, and S is the list of scores for each prompt in P. So the first step is to find best score for each example!

# Best score per example: s*[i] ← max_k S_P[k][i]

s = {}

for ex in D_pareto:

qid = ex.qid

s[qid] = max(

(S.get(k, {}).get(qid, {}).get("mu", 0.0) for k in P),

default=0.0

)Our D_pareto is just the set of examples we use to evaluate the prompt. Last part gave us the best possible score per example, now we need to get the all the prompts that achieve that score

# Instance-wise winner sets: P*[i] ← {P[k]: S_P[k][i] = s*[i]}

P_star = {}

for ex in D_pareto:

qid = ex.qid

best_mu = s[qid]

winners = []

for k in P:

mu_k = S.get(k, {}).get(qid, {}).get("mu", 0.0)

if abs(mu_k - best_mu) < 1e-9:

winners.append(k)

P_star[qid] = winnersI use scoring as that is calculated for each example. So now we have for each example, the best prompts that achieve the highest score for the prompt. Notice that this can be multiple prompts if many prompts have the same highest score for the same example.

C = set()

for winners in P_star.values():

for cand in winners:

C.add(cand)After getting the unique prompts from the list of all prompts that were the best for some example, we prune the “dominated” prompts. Prompt is dominated, if for all the examples, there exists prompt which is at least as good, but at least for one prompt it is better. So basically if one prompt is always better than other prompt, we discard it!

# Prune dominated → P_optimal

P_optimal = prune_dominated(C, P_star)

if not P_optimal:

P_optimal = Cwhere

def build_winner_sets(P_star: dict[str, list[str]]) -> dict[str, set[str]]:

W: dict[str, set[str]] = {}

for qid, winners in P_star.items():

for k in winners:

W.setdefault(k, set()).add(qid)

return W

def dominates(a: str, b: str, W: dict[str, set[str]]) -> bool:

Wa = W.get(a, set())

Wb = W.get(b, set())

return (Wb.issubset(Wa)) and (Wa != Wb)

def prune_dominated(C: set[str], P_star: dict[str, list[str]]) -> set[str]:

W = build_winner_sets(P_star)

C_list = list(C)

D: set[str] = set()

for i, a in enumerate(C_list):

for b in C_list[i+1:]:

if dominates(a, b, W):

D.add(b)

elif dominates(b, a, W):

D.add(a)

return {c for c in C_list if c not in D}So basically, it is just creating “winner” sets, and checking if one set is subset of another. This works, because in last step we created the set of the best candidates. So if one set is subset, it implies that both set contain some same examples, and another set contains strictly more examples, meaning that the prompt corresponding to that set is better in all the examples.

Lastly we create frequencies of the prompts (how many times it was best in examples)

P_hat_star = {

qid: [c for c in winners if c in P_optimal]

for qid, winners in P_star.items()

}

# f[Φ] = # of i with Φ ∈ P̂*[i]

from collections import Counter

freq = Counter()

for winners in P_hat_star.values():

freq.update(winners)

frequencies = {c: freq.get(c, 0) for c in P_optimal}and use that to pick one by random

# Sample Φ_k ∝ f[Φ_k]

candidates = list(frequencies.keys())

weights = list(frequencies.values())

if sum(weights) == 0:

weights = [1] * len(candidates)

chosen = random.choices(candidates, weights=weights, k=1)[0]

return choseThat’s it! We just choose the best prompts on examples, filter out prompts that are worse than other prompts which gives us list of best prompts in all examples. Then just pick one of those by giving the prompts weight, and taking one randomly by the weights.

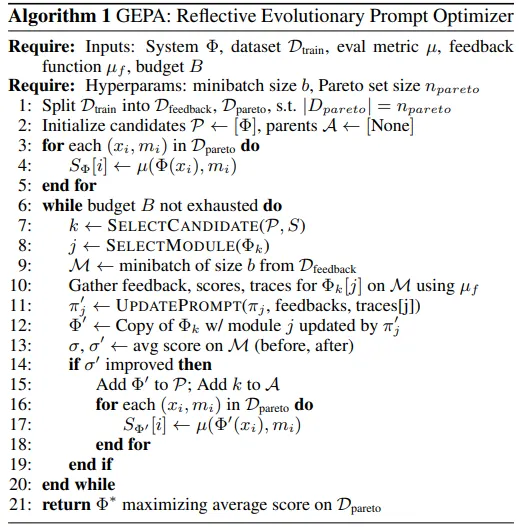

Main loop algorithm

Initialization

OK, now we get to the most important part: how to improve the LLM prompt.

I chose to use DSPy for this, and create my own DSPy optimizer which works like GEPA (DSPy also has full GEPA already implemented, but I chose to build it by scratch).

DSPy optimizers are class of Teleprompter, which needs one method “compile”, which takes the DSPy module (the program we want to optimize), and the training set.

from dspy.teleprompt.teleprompt import Teleprompter

# Main GEPA optimizer

class GEPA(Teleprompter):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Initialization here

def compile(self, student: dspy.Module, trainset: List[Example]):

# Logic hereThe algorithm splits the training set to two distinct sets: and the

D_feedback, D_pareto = self._split_trainset(trainset, n_pareto)Feedback set is used to gather feedback for the prompt, and pareto set is used to evaluate the performance of different prompts.

The first step is to get the base performance of the system we want to optimize for. This can then be used to compare if our new candidates are better than the original system:

# Get base performance

for ex in D_pareto:

out = student(question=ex.question, context=ex.context)

pred = out["answer"]

em = exact_match(pred, ex.gold_answer)

f1_ = f1(pred, ex.gold_answer)

mu = 0.7 * f1_ + 0.3 * em

S["base"][ex.qid] = {"em": em, "f1": f1_, "mu": mu}Then we need to get the information about the system we want to optimize for, e.g. the module names and list of initial candidates (prompts)

names = self.module_names(student)

candidate = self.snapshot_candidate(student)

candidates: Dict[str, Dict[str, str]] = {"base": candidate}While loop

If you look at the algorithm, we now have everything to start the main while loop that is in the algorithm.

For each iteration

iteration = 0

while iteration < B:

# Logic here

iteration += 1we select the candidate (pareto-based candidate selection), and module we want to optimize (round-robin)

k = select_candidate(D_pareto, P, S)

current_candidate = candidates[k]

module = names[iteration % len(names)]Create minibatch (small subset of the ) to gather feedback from

minibatch = random.sample(D_feedback, minibatch_size)Then we create the new program containing our prompt and run that. After running and getting the output, we can give feedback function the outputs that the model gave in our program:

for ex in minibatch:

output = instrumented_student(question=ex.quetion, context=ex.question) # Student program which also logs inputs and outputs of individual modules

# Gather all the info you want to send the feedback function:

# e.g.f1_metric = f1(output['answer'], ex.gold_answer)

fb = self.feedback(f1_metric, module_name, question, context) # Get the feedback, give it context of the last call

fb_content = {

"input": latest_inputs["inputs"],

"output": latest_inputs["outputs"],

"feedback": fb

}

feedbacks.append(fb_content)

The last example doesnt contain all the steps due to being bit verbose. However, the basic idea is simple. You need to run the newly created program on the minibatch, then gather information of how it works on the minibatch (inputs, outputs, final score, module we optimize for, etc.) and then run another LLM call which analuzes all of this information and gives feedback on how the model did on example:

Here’s mine feedback gathering signature:

class Feedback(dspy.Signature):

"""Given a module's instruction, its input/output on one example,

and the correct answer of the multi-step LLM process. Suggest how to improve

the instruction. Be brief and concrete."""

module_name = dspy.InputField()

instruction = dspy.InputField(desc="Current instruction for this module.")

# Example-specific context (for the judge to look at)

question = dspy.InputField()

context = dspy.InputField()

module_output = dspy.InputField(desc="What this module produced on this example.")

final_answer = dspy.InputField(desc="Program's final answer on this example.")

gold_answer = dspy.InputField()

em = dspy.InputField()

f1 = dspy.InputField()

feedback = dspy.OutputField(

desc="1-3 short bullet points telling how to adjust the instruction."

)Now we have list of feedback from the examples we run. These are all example specific feedback, e.g. what went wrong on that single example. So the next step is to analyze the feedbacks. So we give anohter LLM call all the input, output, feedback triples. This module then generates the new improved prompt based on the information provided.

new_instructions = self.update_prompt(

curr_instructions=current_candidate[module],

feedbacks=feedbacks

)where update_prompt basically just calls the DSPy signature for creting new prompts:

class UpdateInstruction(dspy.Signature):

"""I have given an assistant instruction to perform a task for me.

You are given:

- The current instruction given to the assistant.

- Several (input, output, feedback) triples.

Your task:

- Infer precisely what task is the assistant is expected to solve.

- Use the feedback to refine and improve the correct behaviour.

- Encode all domain-specific constraints and subtle requirements so they are not lost.

- Emphasize, correct answer type and format, using provided context faithfully, avoiding specific failures noted in feedback.

Return ONE self-contained instruction block that replaces the old one.

Do NOT include ``` in the output, output ONLY the new instruction text.

"""

curr_instruction = dspy.InputField()

input_output_feedbacks = dspy.InputField()

new_instruction = dspy.OutputField()As a output, we are given new instruction, which tries to be better than the original we gathered feedback from. So the next logical step is to put the new instruction for the module into the program, and run it on minibatch again.

Now we have run the minibatch on original version of the system, and the new system with updated prompt. We only want to add prompts to our candidate pool if they improve the performance, so we calculate the performance of both systems, and if the performance is better on the new prompt, we add this new system to the candidates and run the final system once again on the set to gather its performance.

old_score = 0.3 * em_old_avg + 0.7 * f1_old_avg

new_score = 0.3 * em_new_avg + 0.7 * f1_new_avg

if new_score > old_score:

new_id = f"{k}+{module}"

P.add(new_id)

candidates[new_id] = new_candidate

# Evaluate new candidate on D_pareto for later comparisons

S[new_id] = {}

for ex in D_pareto:

out = new_student(question=ex.question, context=ex.context)

pred = out["answer"]

em = exact_match(pred, ex.gold_answer)

f1_ = f1(pred, ex.gold_answer)

mu = 0.7 * f1_ + 0.3 * em

S[new_id][ex.qid] = {"em": em, "f1": f1_, "mu": mu}

iteration += 1 # That's it! We run this loop until we have used our main loop budgetLet’s stop for a moment and think what the idea of this main loop is. The main loop is just one while loop that runs budget amount of times. Budget is set by the user and just tells how many times we want to try to get better instruction. Each iteration, we choose one candidate based on pareto-based selection, then we run the program on minibatch while gathering feedback of how it behaves on it. Then we give feedback to another LLM call which tries to improve the module prompt with the feedback.

Finally we create the new system with updated prompt, evaluate it, and if performance improves we add it to the candidate pool. Candidate pool thus increases by prompts that were better in minibatch than the original candidate we chose with pareto-based selection.

After we have run the main loop, we have list of candidates and their performance on the Pareto set. So, the only thing left to do is to pick the best candidate where the performance is the highest!

# Select best candidate Φ* based on average mu over D_pareto

best_id = None

best_score = -1.0

for cid in P:

scores = S.get(cid, {})

if not scores:

continue

avg_mu = sum(v["mu"] for v in scores.values()) / len(scores)

if avg_mu > best_score:

best_score = avg_mu

best_id = cid

if best_id is None:

return student

best_candidate = candidates[best_id]

best_program = self.build_program(student, best_candidate)

print(f"Chosen best candidate: {best_id} with avg mu={best_score:.4f}")

return best_programOutput!

So how well our optimizer then actually did on the HotpotQA that we wanted to optimize for? Well, suprisingly well when compared to the base model!

Base EM: 0.5500, F1: 0.7410

Optimized EM: 0.7000, F1: 0.8619

[Improvement]

Δ EM: +0.1500

Δ F1: +0.1209Our optimized model improved the output of the both EM and F1 score that I used as metrics over 10%! This is quite good considering that I only run the program on the budget of 15 and minibatch of the size 7! Here is basically my main function that run the optimization:

def main():

lm = dspy.LM('openrouter/google/gemini-2.5-flash-lite', api_key=os.getenv("OPEN_ROUTER_KEY"), api_base='https://openrouter.ai/api/v1')

dspy.configure(lm=lm)

program = HotpotModel()

dev = load_examples("validation", limit=20)

train = load_examples("train", limit=70)

print("\n[Base program evaluation]")

base_metrics = evaluate(program, dev)

print(f"Base EM: {base_metrics['EM']:.4f}, F1: {base_metrics['F1']:.4f}")

gepa = GEPA()

optimized = gepa.compile(program, train)

print("\n[Optimized program evaluation]")

opt_metrics = evaluate(optimized, dev)

print(f"Optimized EM: {opt_metrics['EM']:.4f}, F1: {opt_metrics['F1']:.4f}")

d_em = opt_metrics["EM"] - base_metrics["EM"]

d_f1 = opt_metrics["F1"] - base_metrics["F1"]

print("\n[Improvement]")

print(f"Δ EM: {d_em:+.4f}")

print(f"Δ F1: {d_f1:+.4f}")

optimized.save("programs/optimized_hotpot_model.json", save_program=False)Even on small iteration count, and small amount of examples that are used for training, we can improve the base model in all metrics by 10%, personally I’m quite happy on the improvement.

Here’s also the improved prompt that the optimizer found:

From the provided context, identify the bridge fact(s) that directly support the answer to the question. Then, propose a concise answer.\n\n**Constraints:**\n* **Bridge Fact:** The bridge fact must be a direct quote from the context. It should clearly link the question to the answer.\n* **Answer:**\n * The answer must be extracted *exactly* from the context. Do not infer or use external knowledge.\n * If the answer is a person's name, provide the full name if available.\n * If the question asks for a nationality, provide the nationality.\n * If the question asks for a city, provide the city name.\n * If the question asks for a year, provide the year.\n * If the question asks for a yes\/no, provide \"Yes\" or \"No\".\n * Emphasize exact string matching for the final answer.\n* **Rationale:**\n * Provide a rationale that explains how the bridge fact answers the question.\n * The rationale should be 2-4 lines long.\n * If the answer is a yes\/no, the rationale should be a short span.\n\n**Output Format:**\n```json\n{\n \"answer\": \"...\",\n \"bridge_fact\": \"...\",\n \"rationale\": \"...\"\n}\nSummary & Reflections

In this blog I went over on the basics of the GEPA optimizer, and how could a person implement the basic GEPA loop on their own. The ideas behind it are not complex, we have one main loop which chooses one candidate based on pareto front, uses tha candidate to gather feedback, and use the feedback to generate better prompts for the system.

Even this basic GEPA implementation was able to improve the performance considerably from the base system. However, this was just basic example of the GEPA, in the paper, authors also use “merging” of prompts to generate better prompts. Our current one tries to improve the prompt always by gathering feedback and based on that make better instructions, however, with merging, we could take two different candidates and generate one candidate by trying to take best parts of the prompt to one final prompt. The paper found that this even more improved the performance on some tasks.

One final notice! This was just my learning to understand GEPA implementation. GEPA has GREAT github repo for the implementation which has adapters ready for the implementation. DSPy also has ready-made adpater for using the GEPA, so the user doesnt need to understand the insides of GEPA to be able to optimize their prompts. Just simple

gepa = dspy.GEPA(metric=metric, track_stats=True, ...)

new_prog = gepa.compile(student, trainset=my_tasks, valset=my_tasks)is enough to run the full optimization on DSPy.

So after all, prompt optimization is not magic, the ides behind it are simple! Once you see how simple the “one of the best” prompt optimizers are in the core, you realize that teaching LLMS to improve itself is less about clever prompts, but more about better feedback loops.